A loss of fine motor skills is a common symptom of neurologic conditions. Try these creative ways to improve dexterity or adapt to changes.

“I have a lot to lose if I let this disease take away my hand dexterity,” says Schuetz. “Not only the sense of feeling productive, but a bit of my identity, too. It’s important to keep my hand skills up to par.”

Decreased Dexterity

Parkinson’s disease, with its tremors, freezing, and stiffness, is not the only neurologic condition that can cause hand and finger difficulties like Schuetz’s. For people with essential tremor, the shaking worsens with activity. Those with multiple sclerosis (MS) often experience lack of coordination and hand weakness. Dystonia, a movement disorder that causes uncontrollable muscle contractions, can result in twisted posture and cramping, which can affect hand dexterity. Neuropathies may cause numbness and weakness. And about eight out of 10 stroke survivors experience weakness on one side of the body, including the hand, according to a 2014 study in the Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation.

For people with MS, trouble with dexterity can happen at any stage of the disease, says Michael J. Olek, DO, associate professor of neurology at the Touro University Nevada College of Osteopathic Medicine in Henderson, NV. “Patients may have trouble with handwriting, using keyboards, and preparing meals.”

Dearth of Studies

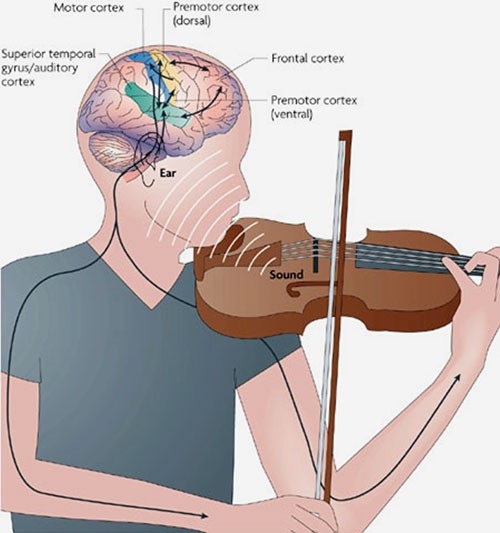

Research on how to improve fine motor skills affected by neurologic disorders is minimal, especially compared with research on aerobic exercise, says Lisa M. Shulman, MD, FAAN, distinguished professor in Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Patients often worry more about improving their walking and balance and less about improving dexterity, Dr. Shulman says. “I think that’s because there are many workarounds for weak hands.” For example, people with poor fine motor skills can buy clothing with fewer buttons and zippers and shoes with easy fasteners, she says. They can also pick up prepared meals so they don’t have to cook.

Still, it’s important to focus on dexterity, Dr. Shulman says. She and patients like Schuetz offer the following advice for retaining dexterity or adjusting to its loss.

8 Ways To Address Dexterity

- Talk to your doctor. Patients are more likely to tell their doctors about problems with walking than loss of dexterity, says Dr. Shulman. “What I’ve observed is that patients who exercise are almost always using their larger muscles, especially in the lower body, when using a treadmill or stationary bike, which preserves lower body function. Meanwhile, their fine motor dexterity disproportionately worsens.” She encourages all patients to inform their neurologists and health care team about any loss of fine motor skills and ask for help in improving and maintaining function.

- Work with an occupational therapist. Physical therapy and speech therapy are more commonly part of a treatment plan than occupational therapy, says Dr. Shulman. “It’s important that neurologists encourage more patients to engage in occupational therapy.” It helps enhance independence, productivity, and safety in all activities related to personal care, leisure, and employment, says Kathy Zackowski, PhD, OTR, senior director of patient management, care, and rehabilitation research at the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

- Consider writing aids. For many people, the simple task of signing a check or restaurant bill or writing a to-do list becomes problematic. To make writing easier, use a pen grip or fatter pens, advises Rick Schrader, 64, a former software salesman in Herndon, VA, who has hereditary ATTR amyloidosis, a rare condition that affects his nerves and hand mobility. His hands get cold easily and lose sensation, but he still balances his business checkbooks every Saturday. “I don’t write fast anymore, but if I take my time I can still write clearly.”

- Write mindfully. Writing quickly and unthinkingly may result in small, cramped handwriting and tightness in your hand, said Dr. Zackowski. “Try not to rush your writing, and switch to print instead of cursive. Using lined paper provides a guide and forces you to use bigger letters, which helps keep writing more legible.” She adds that using a computer keyboard may be easier if you don’t mind typing. And for those who are used to typing but now find it difficult, many keyboard modifications are available, including a key guard that helps users press the key they want without accidentally pressing other keys.

- Use adaptive devices. For assistance when getting dressed, you can use reaching aids, button hooks, zipper pulls, Velcro shoe fasteners, or shoe horns, says Dr. Zackowski. To help with cooking and navigating the kitchen, she recommends tools such as nonskid placemats, utensils with oversized or angled handles, and rocking T knives, which cut food using a rocking motion. In the bathroom, Dr. Zackowski suggests getting a shower chair and a nonskid bath mat and installing grab bars. For grooming, Schrader uses an electric toothbrush and razor. Others may want to install a hands-free hairdryer on the wall or vanity.

- Try different utensils. Poor dexterity can make eating with a fork difficult, says Kathy Villella, who has primary progressive MS. Whenever she eats in a restaurant, Villella orders food such as ravioli that is easy to pick up with a spoon. John Martin, 82, of Independence, MO, who was diagnosed with essential tremor in 2008, uses weighted spoons and knives and eats with his left hand because his right hand is more affected by tremors.

- Keep fit. Staying active is the key to maintaining function and dexterity, says Carolee J. Winstein, PhD, PT, director of the motor behavior and neurorehabilitation laboratory at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Work with your doctor and therapists to find a fitness and exercise plan that will help you maintain function in your hands and fingers.” Schuetz practices yoga, which he says helps him maintain strength and dexterity in his arms and hands.

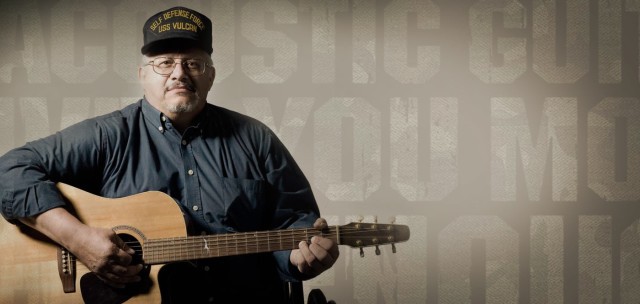

- Improve fine motor skills. To keep his fingers flexible and loose, Schuetz kneads therapy putty, a thick Play-Doh-like paste that varies in pliability from easy to hard. In addition to practicing yoga and kneading therapy putty, Schuetz continues to draw and paint. He says gripping the pencils and paintbrushes strengthens his fingers.

Schuetz also makes rings out of spoons, a hobby he started in the 1970s. Today, it provides another way to stay physically and creatively engaged. He hopes to move beyond rings into small bronze sculptures of yoga poses. “I want to bring together my two main interests—art and yoga—and keep my hands busy and happy.”

Recent Comments