What do we know about the relationship between coronavirus and Parkinson’s?

Joaquim Ferreira, neurologist, Portugal: There is still scarce information regarding many clinical aspects of this infection and its potential short- and long-term complications. We know that the majority of people with Parkinson’s are elderly, and age is a risk factor for the more severe forms of Covid-19. On the other hand, we recognise that patients might be affected indirectly by the lockdown physical restrictions, the psychological impacts and the compromised healthcare.

Miriam Parry, senior Parkinson’s Disease nurse specialist, UK: We do know that people with Parkinson’s are more prone to pneumonia and infections. Parkinson’s can cause respiratory issues for some people – if you have lived with Parkinson’s for a long time, you are more likely to have breathing and respiratory difficulties. This is why people with Parkinson’s are described as being at greater risk of severe illness if they get coronavirus. As such, their caregivers need to take precautions.

Rick Helmich, neurologist, the Netherlands: We know very little, but knowledge is rapidly increasing. Parkinson patients who develop Covid-19 seem to suffer from the same symptoms as other people and to approximately the same degree. However, patients who get sick from coronavirus may suffer from a worsening of their Parkinson symptoms. This is a well-known finding that also occurs when Parkinson patients develop other non-coronavirus infections. The current pandemic also has effects on Parkinson patients that are not so visible, such as increased stress levels and less physical exercise due to the social isolation measures.

How has the coronavirus crisis affected how you and your colleagues carry out your roles, and interact with patients?

Emma Edwards, Parkinson’s specialist nurse, UK: The coronavirus crisis has meant that our face-to-face appointments were stopped with immediate effect. We knew that telehealth technology was due to be implemented in our work area over a planned period of about seven months. When the crisis happened, that roll out took about seven days! In May, I started to see some patients again in their homes. Those allocated for this type of review were people that were running into problems with their Parkinson’s that we couldn’t resolve over the phone or via the virtual clinics.

Helmich: For a few months, I have been working mainly from home, and all my contacts with patients were through video-conferencing and by phone. It took some time to adjust, but I am actually very happy with how it turned out now. It is amazing how much you can see and discuss via a good video connection. On the other hand, more subtle things are better seen in real life, so I am happy that we are allowed to see more patients at our hospital in the next weeks.

Ferreira: The major implications of visit cancellations for patients that were hospitalised, or doing rehabilitation programmes as inpatients, should also be mentioned. This situation forced all health professionals to be involved in facilitating communication and minimising the consequences of not seeing family and friends.

How has the coronavirus crisis affected access to treatment for people with Parkinson’s?

Helmich: This is a topic that many patients are worried about: access to health care. Many Parkinson patients are treated by a whole team of professionals, including a neurologist, a Parkinson nurse, a physical therapist, and sometimes a psychiatrist, speech therapist, or occupational therapist. Access to these health care providers has been restricted by the isolation and social distancing measures. Not all people have good access to internet, and not all treatments can be given through video conferencing. So, I believe that the care for Parkinson patients has certainly suffered from the coronavirus pandemic.

Ferreira: The coronavirus pandemic severely affected the follow-up of people with Parkinson’s disease. The regular consultations were cancelled, making it more difficult or impossible the access to physicians and other health professionals. Pharmacological prescriptions were more difficult to obtain. Sessions of physiotherapy, speech therapy and other therapeutic interventions were cancelled, and physical activity and exercise was highly reduced for many patients. Many deep brain surgeries were deferred, and patients included in research studies and clinical trials saw their consultations being moved to phone contacts or videocalls.

Edwards: Face-to-face sessions such as our Parkinson’s exercise groups, have also been postponed but luckily the staff that ran those groups produced a brilliant DVD of the common exercises they undertook in class. These were distributed out to homes at the beginning of the outbreak and were warmly received by many people with Parkinson’s.

What actions should people with Parkinson’s take at the moment?

Ferreira: The most important recommendation for people with Parkinson’s and their close friends and family is to follow the general public health recommendations that apply to the elderly population. At the current stage of the pandemic, when governments are lowering the confinement measures, the most important message is to alert everybody that this pandemic is not over and the general measures that are being recommended for the general population should be followed strictly in the next months.

Parry: When you leave the house, for any reason, you should avoid busy spaces and keep a distance of around two meters from people you do not live with, while wearing a face mask. You should also continue to follow good hygiene practices, including handwashing, not sharing crockery and cutlery, wiping down surfaces, and not entering other people’s homes. You can ask your local pharmacist to deliver medication to your home address or ask family members or friends to help.

Edwards: I would really advocate for people, if they can, to exercise. It has proven benefits not just for physical health in Parkinson’s but for promoting good mental health. I’ve been really impressed with the exercise classes available online to people with Parkinson’s whilst the group classes have been postponed.

What should people with Parkinson’s do if they have hospital and GP appointments during this period?

Parry: If you’re in the UK, please call the GP’s practice and ask for further information and direction pending the reasons for the appointments. The GP practice will be able to advice you whether it is urgent or offer you a phone or video consultation. Routine hospital appointments have now changed to virtual clinics using phone and video link consultations.

Ferreira: During this crisis, health institutions in Portugal have changed their procedures in order to implement safety circuits for those who will need to attend their routine visits or need to go to the hospital in an urgent situation.

Edwards: I would imagine as we come out of the lockdown, clinical outpatient appointments in the UK will look very different to what people are used to. Certainly, in our area, personal protective equipment will be worn by staff and visiting patients are encouraged to wear face masks. If people with Parkinson’s need advice on managing their condition and are not sure when their next review will be, they should contact their local Parkinson’s service and ask for help. Be proactive!

How can people with Parkinson’s look after their mental wellbeing?

Ferreira: All health professionals that follow patients with Parkinson’s recognise that this has been a difficult time, not just for the patients but for all around them. The most important thing for the community is strengthening support and continuing care, keeping the links between patients, their families, caregivers and health professionals.

Helmich: This is different for everyone. Some of my patients even like certain aspects about the current situation, such as a reduction in workload, deadlines, or social obligations. In general, I think it is good to try to stay in touch with your loved ones. Find a new structure for your day that works for you and develop new exercise routines. There are many online events available for Parkinson patients, such as online dancing or singing classes. So, it might be worthwhile to have a look online to see what is out there or ask someone to help you do so. Don’t be afraid to speak about your worries or fears.

Edwards: Being able to connect with others has been a challenge during the lockdown, but as restrictions are eased, I really encourage people to meet others again, albeit in a safe way. For many during coronavirus, that has been via online forums like Zoom or having a socially distanced chat over the garden fence to family and friends. I’m also a massive advocate for mindfulness. It’s a way to be fully present, having an awareness of where we are and what we are doing and feeling, without being overwhelmed by what’s going on around us.

Parry: It is normal and expected to feel a range of emotions during this pandemic including fear, increased anxiety, anger and sadness. There is guidance on looking after mental wellbeing during this time from mental health charity Mind, as well as support on the Parkinson’s UK and Parkinson’s Foundation websites.

What is the advice for those living with a vulnerable person?

Parry: Visitors and people who provide care for those with Parkinson’s should protect them and reduce their risk by staying at home as much as possible. They should work from home, if they can, and limit contact with other people.

Ferreira: It is a good principle to assume that everybody who we are in contact with may be infected, even if they don’t present any suspected symptoms. No one can be sure that they are not infected or do not have a risk of infecting others. This is even more relevant for health professionals, caregivers, family members and those that have close contact with vulnerable populations.

Edwards: I knew from the moment I re-started my home visits that I had not fully been picking up the impact that the coronavirus and subsequent lockdown has had on care partners. It was harder to pick up the subtleties of care partner stress on the telephone or even on the telemedicine appointments. I’m certainly more mindful that we need to continue to address this area as digital medicine becomes more accessible for people with Parkinson’s and potentially less contact is had with partners or carers during these interactions.

Helmich: Be aware that vulnerable people are sometimes less able to cope with new or threatening situations. Be patient if your loved ones are anxious, worried, or experience a worsening of their symptoms.

Do you think the coronavirus crisis will have a long-term impact on people with Parkinson’s?

Ferreira: The limitations induced by the Covid-19 pandemic are here to stay and we need to be prepared to adapt for the next months.

Parry: The Covid-19 pandemic could potentially have a long-term impact on the physical and mental health of people with Parkinson’s, and many studies are currently taking place looking at the effect of this pandemic.

Edwards: I think lots of clinicians were hoping that we could eventually use technology in how we review our patients, and this crisis has pushed that to the forefront. I like being able to offer our patients a wider range of ways that they can access information and advice – from virtual clinics to wearing digital technology – but also being able to offer more traditional face-to-face home visits if needed.

Need to knowEmma Edwards: I’m a mental health nurse in the UK – however for the last 10 years I’ve worked as a Parkinson’s specialist nurse in the community. I had worked in a large rural area for many years, but more recently have moved to a post in a city. Due to the lockdown on clinical work environments, my dining room is currently my office!

Joaquim Ferreira: I am a neurologist mainly working in the field of Parkinson disease for the past 25 years. I am also professor of neurology and clinical pharmacology at the University of Lisbon, Portugal. More recently, I founded CNS, Campus Neurológico Sénior, which is a movement disorders centre focused on the multidisciplinary care and rehabilitation for Parkinson’s patients.

Miriam Parry: I work as senior Parkinson’s Disease nurse specialist (PDNS) at King’s College Hospital NHS, Parkinson’s Foundation Centre of Excellence in London, UK. My role is to provide a holistic approach to care and seamless service to people with Parkinson’s and their family and carers, providing ongoing support, educating and empowering patients to become experts in their condition. Above all, I aim to engage people with Parkinson’s with King’s rich research portfolio on offer, as without it we would not have the knowledge and the care pathways that we do.

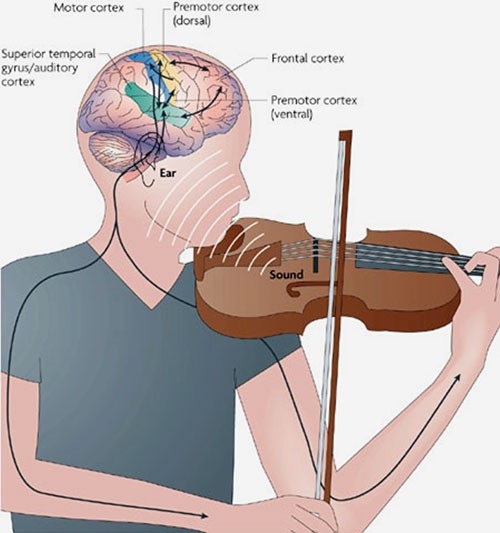

Rick Helmich: I live in Nijmegen, the Netherlands and work as a neurologist and neuroscientist at the Radboud University Medical Centre. I specialise in Parkinson’s, and in my research at the Donders Institute, I use brain imaging to help understand symptoms and phenomena I see in my patients. Lately I’m intrigued by the effects of stress on patients with Parkinson’s, both the causes and the consequences.

Information from Parkinsonlife.eu.

Recent Comments